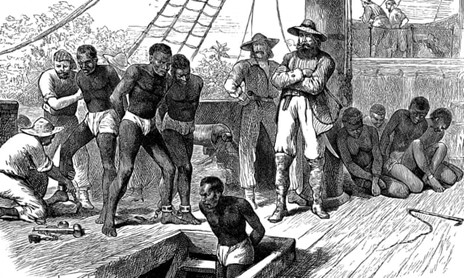

Samuel Jackman Prescod was born in 1806 on the British West Indian island of Barbados, as a person of colour. He was born the year before the abolition of the slave trade, at a time when the fight for change was raging. The move that would ultimately lead to the end to slavery was being waged, and 1807 can be considered as the first shot across the bow, the first assault on the system that would finally come to a legal end on August 1, 1838.

The thrust for the end of the British transatlantic slavery, like any war, would ultimately be won in stages, incremental battles, and Samuel Jackman Prescod would give his life to the struggle for ‘full legal equality’ across the people groups

of Barbados. He first came to public notice in 1829, when, as a twenty-two-year-old young man, he was very vocal at a meeting convened by the Free-Coloured people of the island. This forum was organized in an effort to draft a petition to

the legislature, related to the rights and privileges concerning this group. As a free-coloured man himself and living under the restrictions of that group, he was

incensed and critized the leaders of the group, contending that the demands being made did not go far enough to reflect their rights as free people. Even at this stage in the game he wanted to see a fully integrated equality. To this end, he

would later use the tools of his journalistic skills and opportunities as Editor of the Liberal newspaper to agitate for the rights of all the deprived people of this

land. From this journalistic platform his was a prominent voice, as he spoke out about the ills of the society and encouraged the disenfranchised in the struggle

for human rights.

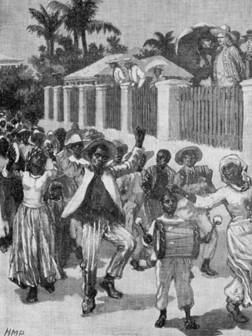

In the ensuing years Prescod would dedicate his life to the fight for equal rights under the law, for the dispossessed of this island. Even in 1838 when emancipation (‘full freedom’) was legally granted to the enslaved, he raised his voice in an article in the Liberal newspaper, admonishing the powers that be, to recognize that it was not enough to deliver freedom on paper but freedom with all the attendant rights that came with that status. To keep the flame of justice for all

alive, Prescod would move his participation in the campaign for human rights to the floor of the House of Assembly, where he sat as the first non-white member to be elected. He served the city of Bridgetown in that capacity from June 6, 1843, until 1860. During his time in the House of Assembly, Prescod became leader of the Liberal Party. On completing his service in the House, Samuel Jackman was not done and went on to serve as a judge on the Assistant Court of Appeal and later the Appeals Court of Barbados. Long after his death Barbados honoured Prescod by placing his image on Barbados currency and in 1969 his name was attached to the educational institution of the Samuel Jackman Prescod Polytechnic (SJPP), now the Samuel Jackman Prescod Institute (SJPI).

Honour and justice were the keystones of the character of Samuel Jackman Prescod. He was described as ‘the greatest Barbadian of all time.’ He lived a life of integrity and was consistent in his work to absolve the disenfranchised from

the yoke of injustice. He committed his life to this struggle and gave his life in service to the people of Barbados. Samuel Jackman Prescod died on September 26, 1871, and in the newspaper, the Agricultural Reporter, he was lauded by his

adversaries, the white elite planter-class. They applauded him as a man of strength who had fought the battle, the battle that his class would never again be required to fight, because he had fought the battle and won. The impact of his work remained and in 1998, one hundred and twenty-seven years after his death, he was further saluted as he was inducted into the pantheon of national heroes of Barbados. Along with the other heroes, his likeness has been set in the National Heroes Square in the capital of Bridgetown. He has been recognized and honoured in ways that are all befitting of his life’s work.

Long live the memory of the sacrifices and arduous work done by the Right Excellent Samuel Jackman Prescod, in his quest for justice that would redound in change.